Welcome back! If you’ve been following along our journey through the world of Java proxies, you know we’ve spent a lot of time learning about the Proxy pattern and how it is used, its uses in various large libraries in the Java world, and even created a dynamic proxy using Java’s internal feature: The JDK Dynamic Proxy.

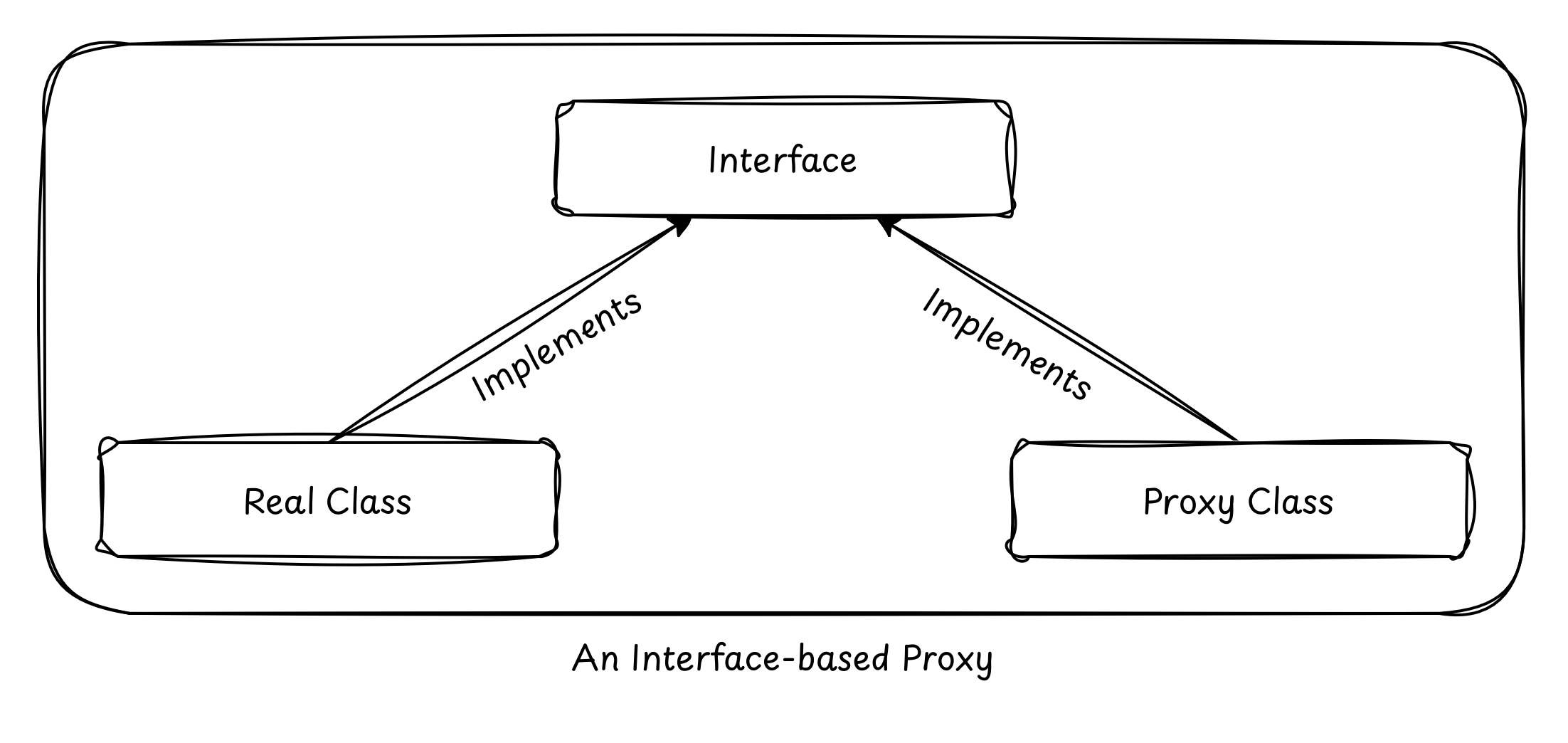

While using JDK Dynamic Proxies is easy… after all, they’re built right into the JDK! You don’t have to import any third-party library in order to create a dynamic proxy. They are convenient and they are reliable… but, they’re a bit too restrictive. They only work with interfaces.

What if the class you want to proxy doesn’t implement an interface? In that case, the JDK is going to look at your face and politely decline to help. But in the real world of Hibernate entities, Spring beans, and legacy monoliths, we often need to proxy classes directly. To break this interface barrier, we have to move away from high-level Java and start playing with the actual bytecode that makes up our classes.

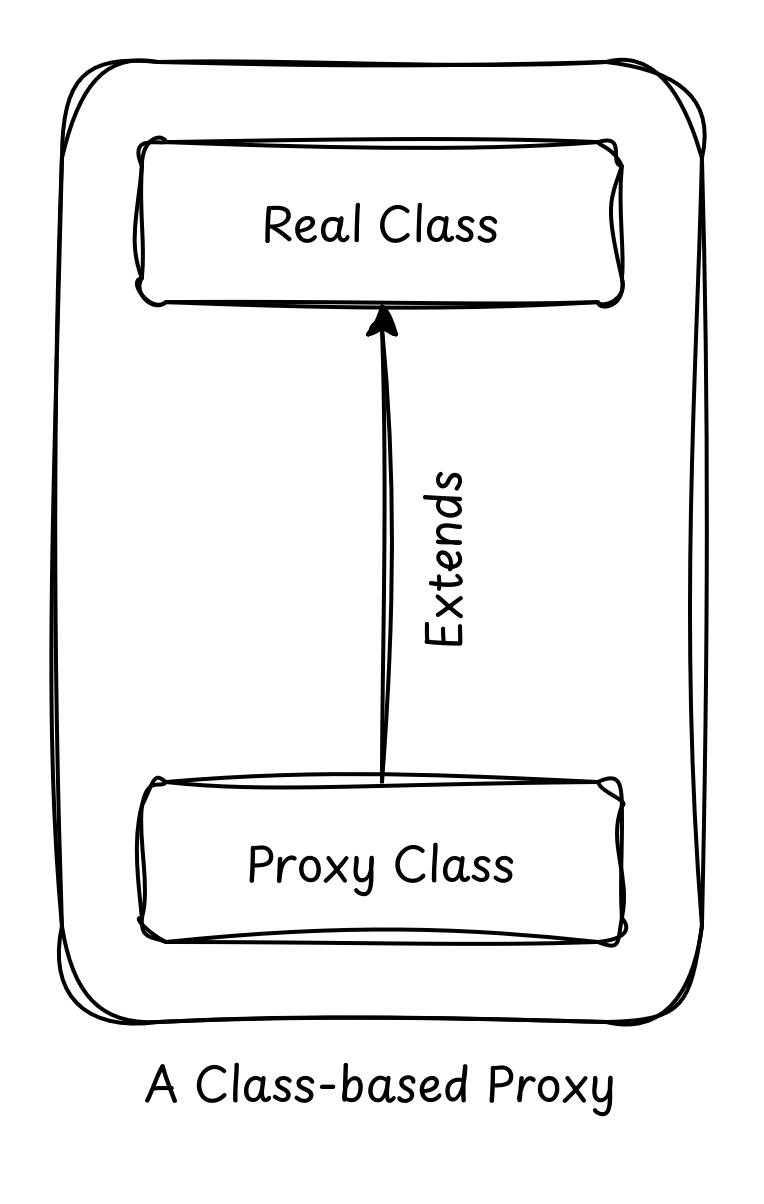

Class-based Proxies

If you can’t use an interface to define a proxy, how do you do it? The answer is surprisingly simple in theory: Inheritance. Instead of creating a sibling class that shares an interface, we create a child class at runtime. This child class overrides the methods of the parent and inserts the extra logic (logging, transactions, security) before calling super.method().

By becoming a subclass, the proxy is now an instance of the original class (thanks, polymorphism!), allowing it to be injected anywhere the original was expected. This is the bedrock of most Java frameworks, which rely on this “invisible” inheritance to add powerful features without forcing you to change a single line of your domain logic.

But this capability didn’t appear overnight. Before we reached the modern landscape of bytecode engineering, the Java community relied on a singular, powerful tool to bridge the gap where the JDK fell short. To understand where we are going with modern solutions, we first have to look at the library that paved the way and defined an entire era of enterprise Java development.

The history of CGLIB: The Fallen Giant

For over a decade, CGLIB (Code Generation Library) was the undisputed king of class-based proxies. If you’ve ever looked at a stack trace in a Spring Boot application and seen something like UserService$$EnhancerBySpringCGLIB$$…, you’ve seen CGLIB in action.

CGLIB sat on top of ASM, a very low-level bytecode manipulation library. It provided a “high-level” (at the time) API to generate subclasses on the fly. Its most famous tools were the Enhancer class and the MethodInterceptor interface.

While revolutionary, CGLIB is now considered “legacy”. It hasn’t kept pace with the rapid evolution of Java. Since Java 9, the JVM has become much more restrictive about illegal reflective access, and CGLIB’s internal reliance on older ASM versions and dirty tricks for class loading started to cause headaches for developers moving to modern runtimes.

The “Unsafe” instantiation

One of the most notorious “dirty” tricks CGLIB employed (and a primary reason it has struggled with modern Java versions) is its use of the sun.misc.Unsafe API to instantiate proxy classes by skipping constructors entirely.

To understand why this is a “trick,” we have to look at how Java normally handles objects. Usually, when you extend a class, your constructor must call super(). But what if the parent class doesn’t have a default constructor? Or what if the constructor does something heavy, like opening a database connection or throwing an exception?

CGLIB wanted to create a proxy without triggering any of that parent logic.

Here is a simplified look at the kind of “dirty” logic happening under the hood when you use CGLIB to proxy a class with a “difficult” constructor:

import sun.misc.Unsafe;

import java.lang.reflect.Field;

public class DirtyInstantiator {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

// 1. Access the "Unsafe" instance via reflection

// (It's private, so we have to cheat)

Field f = Unsafe.class.getDeclaredField("theUnsafe");

f.setAccessible(true);

Unsafe unsafe = (Unsafe) f.get(null);

// 2. Imagine 'ProxyClass' is the subclass CGLIB generated

// We can create an instance of it WITHOUT calling the constructor

// even if the constructor is private or throws an exception!

TargetClass proxyInstance = (TargetClass)

unsafe.allocateInstance(TargetClass.class);

proxyInstance.doSomething();

}

}

class TargetClass {

public TargetClass() {

// This code will NEVER run when CGLIB uses the 'Unsafe' trick

throw new RuntimeException("You cannot instantiate me directly!");

}

public void doSomething() {

System.out.println("Wait... how am I running? My constructor failed!");

}

}

This technique is considered dirty for several reasons that affect the stability and security of your application:

- Violates Language Guarantees: Java guarantees that a constructor will run before an object is used. By skipping it, CGLIB can leave internal fields uninitialized (null), leading to unpredictable

NullPointerExceptionerrors later in the execution flow. - Encapsulation Breaking: It relies on

sun.misc.Unsafe, an internal API that was never meant for public use. Starting with Java 9 and the Module System (Project Jigsaw), the JVM began strictly “encapsulating” these internals. - Security Risks: If a class has security checks in its constructor to prevent unauthorized instantiation, CGLIB’s trick bypasses those checks completely.

- JVM Fragility: Because this relies on internal JVM behavior, an update to the OpenJDK can (and often does) break this logic, leading to the “Illegal Reflective Access” warnings that have plagued Spring developers for years.

Modern libraries like Byte Buddy still have to deal with constructor issues, but they prefer using documented, “cleaner” ways to handle class definition, or they provide much more transparent ways to handle the super() call requirements.

While Unsafe allowed CGLIB to perform technical miracles, they also turned the library into a “black box” that grew increasingly fragile as the Java platform matured. This fragility eventually created a vacuum in the ecosystem for a tool that could handle the raw power of bytecode manipulation without resorting to the “dirty” hacks of the past.

This is precisely where the industry shifted. We moved away from libraries that try to trick the JVM and toward a framework that works with the JVM’s rules while providing a developer experience that feels like modern, idiomatic Java.

Introducing Byte Buddy and the Fluent API

If CGLIB is the aging rockstar of the 2000s, Byte Buddy is the modern virtuoso. Created by Rafael Winterhalter, Byte Buddy won the “Bytecode Wars” because it realized a simple truth: writing bytecode shouldn’t feel like writing assembly. It should feel like writing Java.

The Philosophy: Type Safety and Simplicity

Byte Buddy’s philosophy is built on moving away from the “stringly-typed” and reflection-heavy approach of CGLIB. Instead of passing strings or raw method objects around and hoping for the best, it uses a Fluent DSL (Domain Specific Language). This allows you to describe what you want the class to do in a way that the compiler can actually understand and validate, catching potential errors before your application even starts.

Unlike its predecessors, which often felt like a black box of runtime magic, Byte Buddy is designed to be predictable. It doesn’t try to hide the fact that it’s generating a class; instead, it gives you a powerful, transparent set of tools to define exactly how that class should behave, ensuring compatibility with modern Java versions and the Module System.

The Fluent DSL: Subclass, Method, Intercept

To create a proxy in Byte Buddy, you follow a flow that reads like a sentence:

subclass(Target.class): “I want a new class that extends Target.”method(ElementMatcher): “I want to target these specific methods.”intercept(Implementation): “When those methods are called, do this.”

ElementMatchers: The “SQL” of Methods

One of the most powerful features of Byte Buddy is the ElementMatchers library. Instead of messy if statements, you select targets using declarative syntax like named("save"), isPublic(), or isAnnotatedWith(Transactional.class). These are composable using .and() and .or().

Hands-on: Intercepting a UserService

Let’s build a real-world example. We have a UserService and we want to measure the execution time of the save() method.

Here is a minimal implementation that includes a basic dependency (a logger or simulated database) and a method that we can easily target for interception.

public class UserService {

// A concrete method with logic we want to 'wrap'

public String save(String username) {

System.out.println(">>> UserService: Persisting user '" + username + "' to database...");

try {

// Simulate some network or disk latency

Thread.sleep(200);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

return "SUCCESS: " + username + " is now in the system.";

}

// A method we might want to ignore or match differently

public void delete(String username) {

System.out.println(">>> UserService: Deleting user '" + username + "'...");

}

}

Here, we implement the Interceptor, which is roughly equivalent to InvocationHandler we wrote while creating a JDK Dynamic Proxy. The Interceptor defines the “extra” logic that we want to inject in our proxy.

import net.bytebuddy.implementation.bind.annotation.*;

import java.lang.reflect.Method;

import java.util.concurrent.Callable;

public class PerformanceInterceptor {

@RuntimeType

public static Object intercept(

@Origin Method method, // The method being called

@SuperCall Callable<?> zuper // The original method logic

) throws Exception {

long start = System.currentTimeMillis();

try {

return zuper.call(); // Execute super.save()

} finally {

System.out.println(method.getName() + " took " + (System.currentTimeMillis() - start) + "ms");

}

}

}

Let’s dig into the code a bit:

@Origin Method method: This is the standardjava.lang.reflect.Methodobject. It is Byte Buddy’s way of handing you the “metadata” of the method being called. You can use this object to access the method name, its annotations, or its parameters without you doing any manual reflection.@SuperCall Callable<?> zuper: This is the real secret sauce. Byte Buddy creates a special auxiliary class that knows how to call the original method in the parent class. By wrapping it in aCallable, you can decide exactly when, or even if, the original logic should execute.- The

try/finallyblock: This ensures that even if the original method throws an exception, our timer still finishes. It is the standard way to implement reliable “around advice” in the AOP world.

The last step is actually creating the proxy using Byte Buddy. Here we instruct JVM to build a new type.

UserService proxy = new ByteBuddy()

.subclass(UserService.class)

.method(ElementMatchers.named("save"))

.intercept(MethodDelegation.to(PerformanceInterceptor.class))

.make()

.load(UserService.class.getClassLoader(), ClassLoadingStrategy.Default.INWRAPPER)

.getLoaded()

.getDeclaredConstructor().newInstance();

proxy.save("Alice");

In the above snippet:

.subclass(UserService.class): This tells Byte Buddy to generate a new class in memory that extends ourUserService. To the JVM, this new class is a legitimate child of the original..method(ElementMatchers.named("saveUser")): Think of this as a filter. Byte Buddy iterates through all methods available in the subclass and only applies our “advice” to the ones that pass this test..intercept(MethodDelegation.to(PerformanceInterceptor.class)): Here, we are “binding” the matched method to our interceptor. Byte Buddy is smart enough to see the annotations in our interceptor and figure out how to pass the right arguments into it at runtime..load(...): This is the bridge to the JVM. We have the bytecode in a byte array, but to use it, we need to define it through aClassLoader. TheINWRAPPERstrategy is the most common approach, as it loads the proxy in a child class loader of the original class, preventing class-loading conflicts..getLoaded().getDeclaredConstructor().newInstance(): Finally, we treat the generated class like any other Java class. We grab its constructor and create an instance. This instance is what we pass around our application, and because of polymorphism, everyone thinks it’s just a regularUserService.

Did you notice that we only proxied the save() method of UserService and not the delete()? Well this is another advantage of using Byte Buddy.

In a JDK proxy, you are forced into a single InvocationHandler where you must handle every method call (including toString, equals, etc.) in one giant switch or if block. Byte Buddy allows you to be surgical. You can apply different interceptors to different methods within the same proxy definition.

Why Byte Buddy is the current standard

When you run the code above, Byte Buddy generates a class at runtime that effectively overrides the save method. But unlike CGLIB, Byte Buddy’s generated code is highly optimized. It uses “Inlining” where possible and avoids the heavy overhead of reflection during every method call.

Furthermore, Byte Buddy handles the complexity of Java’s Module System (Project Jigsaw) gracefully. It knows how to “open” packages or define classes in a way that doesn’t trigger security exceptions on modern JVMs (Java 11, 17, and 21).

In the next part, we’ll look at how these libraries handle “Redefinition” and “Rebasing”—techniques that allow you to modify existing classes rather than just creating subclasses. This is where we move into the territory of Java Agents and serious performance monitoring tools. For now, try running the Byte Buddy example and see if you can add a matcher that intercepts all methods except for those starting with “get”.